Reading done on October 13 2018

"Who disseminates Rumiyah?

Examining the relative influence of sympathiser and non-sympathiser Twitter users"

- by Daniel Grinnell (Cardiff University), Stuart Macdonald (Swansea University), David Mair (Swansea University) and Nuria Lorenzo-Dus (Swansea University)

- This paper was presented at the 2nd European Counter Terrorism Centre (ECTC) Advisory Group conference, 17-18 April 2018, at Europol Headquarters, The Hague.

- the screenshots of the tables above are from report (pages 13, 14,15 (consecutively)).

In this study, Grinnell et al.(2018) examine the release of 9 issues of Rumiyah magazine on Twitter (2-3).

In this research, they raise 2 questions:

- their "previous pilot study suggested that pro-IS throwaway accounts were only creating a small splash on Twitter. Has this been the case for Rumiyah? Are these pro-IS account being disrupted effectively, before they manage to exert much influence?"

- "What is the relative influence of the pro-IS throwaway accounts in comparison to other accounts that are not sympathetic to IS but nonetheless disseminate its propaganda - whether that be for research purposes, personal interest or even to provide an oppositional voice or engage in debate?

In other words, how great is the ripple effect generated by these non-IS sympathiser accounts"

"The fact that most suspended original linker accounts were very young and had only a small – or non-existent – social network suggests that they were set up specifically to advertise the release of the new issue, particularly when coupled with the additional fact that 14.5% of suspended original linkers had never posted before (and a further 32.4% had posted only four or fewer tweets previously)" (Grinnell et al. 2018, 9).

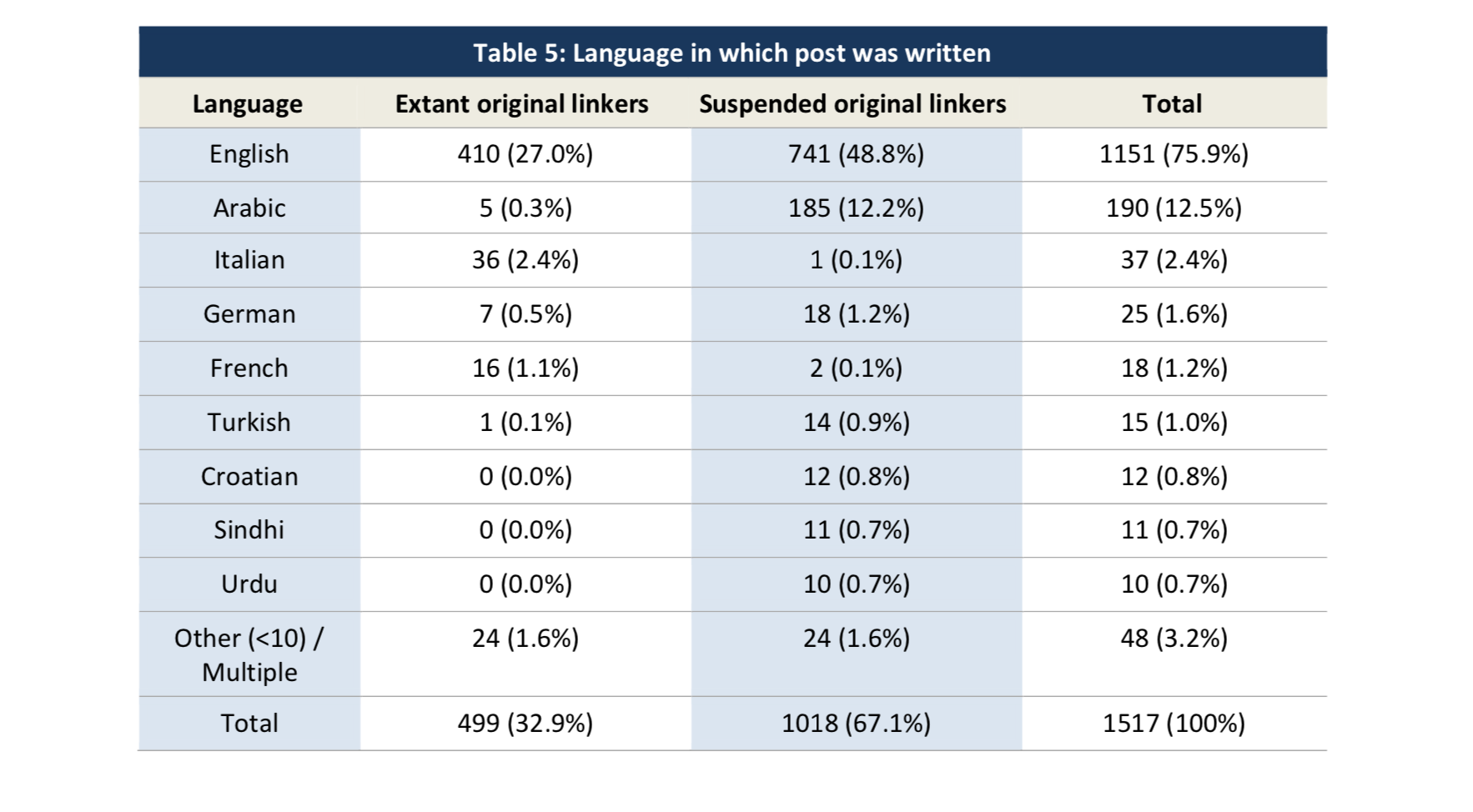

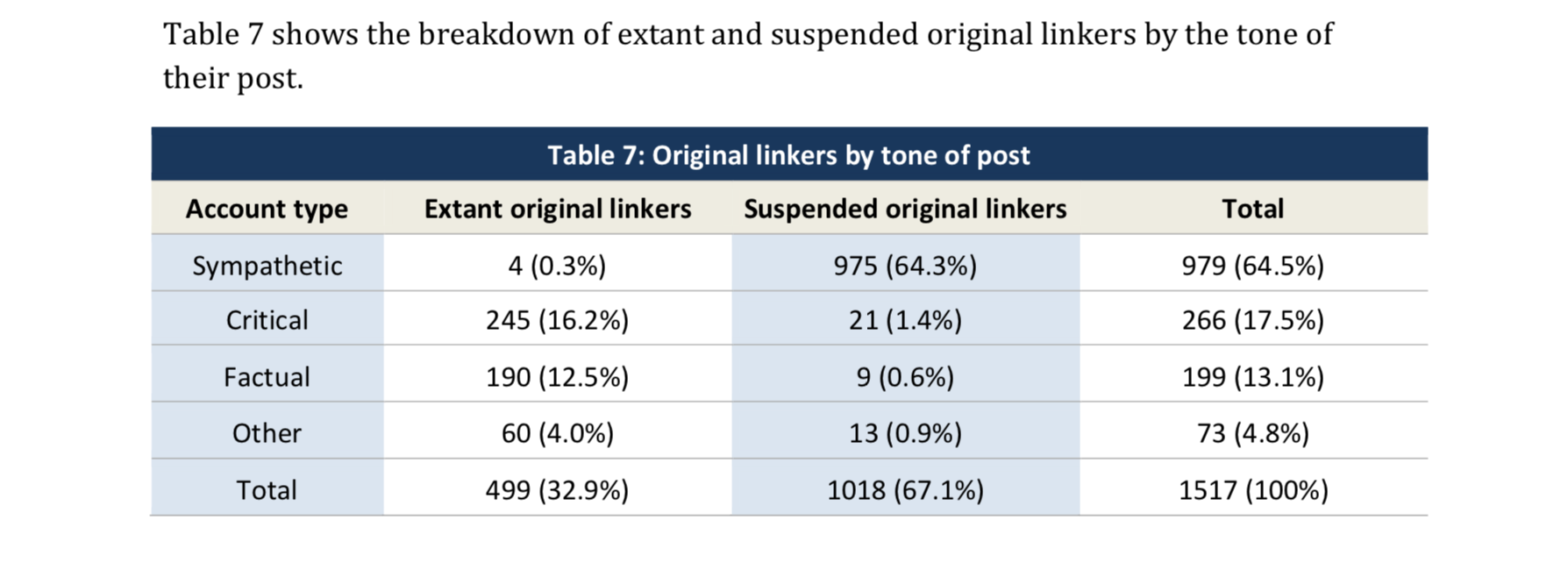

"To return to the two sets of research questions that we identified at the outset, we found that most of the suspended original linkers (i.e. user accounts that posted original content, including an out-link, and were suspended by the end of our data collection period) were sympathetic to the message of Rumiyah. The usernames of these accounts were commonly randomised collections of letters and numbers, the out-links they shared were generally to content-sharing websites (presumably containing e-copies of the magazine or excerpts from it), and whilst most posted in the English language there was also a significant proportion that tweeted in Arabic. Importantly, as in our pilot study, these accounts caused only a small splash: they were normally young accounts (often less than one day old), with very few followers (or none at all) and received few retweets. They thus appeared to be throwaway accounts, that sought to compensate for their lack of visibility by repeat posting" (Grinnell et al. 2018, 16).

"The other sub-group that we have examined, extant original linkers (i.e. user accounts that posted original content, including an out-link, that were still extant at the end of our data collection period), had quite a different overall profile. They mostly posted in the English language and tended to be the accounts of private individuals, intelligence analysts or practitioners, or news/media organisations. They were generally older accounts, with higher numbers of followers, and were less likely to engage in repeat posting. Their tweets were generally either factual in tone or critical of IS, and they out- linked to a more diverse range of sources, including news reports, commentary and analysis, and activist sites and blogs (Grinnell et al. 2018, 16).

"[W]e conclude by suggesting that further research that investigates the identifying features of terrorist propaganda that is particularly successful in provoking a response from the audiences it targets would make a valuable contribution to efforts to disrupt the spread of such propaganda and promote alternative narratives" (Grinnell et al. 2018, 17).